The camera is one of the most important features in a smartphone — we use it to capture memorabilia, to video chat, to share funny sights in our Instagram stories, show off the ‘fit, or whatever else. Sure, some users have other priorities — camera often ranks third on the importance list, behind battery life and display. But, it’s a huge part of the device, and there’s a good reason why most of us no longer own a point-and-shoot camera.

But what are we even looking for? What makes a bad smartphone camera bad and a good smartphone camera good? Don’t they all use Sony sensors?

Well, mostly yes. But since small sensors and small lenses can only capture so much light, smartphones rely heavily on software to clean up, sharpen, and enhance the photos. It has become a reality of modern times that we are mostly judging the software post-processing that a smartphone does automatically, instead of the actual hardware.

Our camera tests

Dynamics

Dynamics refers to the difference between the lightest area and the darkest area in a photo — respectively called “highlights” and “shadows”. When a smartphone has a “wide dynamic range” it means it can capture more details in the light area, and still show objects in the shadows.

If a smartphone has a “narrow” dynamic range, you may spot one of two (or both) unpleasant effects. “Burned highlights” means that anything that is bright in the photo becomes a huge white blotch, with no discernible objects or details. Instead of a cloud, you see a white sky. Instead of a lightbulb, you see a big aura of light. “Crushed shadows” means that the dark areas of the photo simply appear black — no objects or silhouettes get captured.

Of course, every camera has a limit on how far it can go with its dynamic range — bigger sensors with big lenses can do better at this. Smartphones rely on our next point of discussion:

HDR

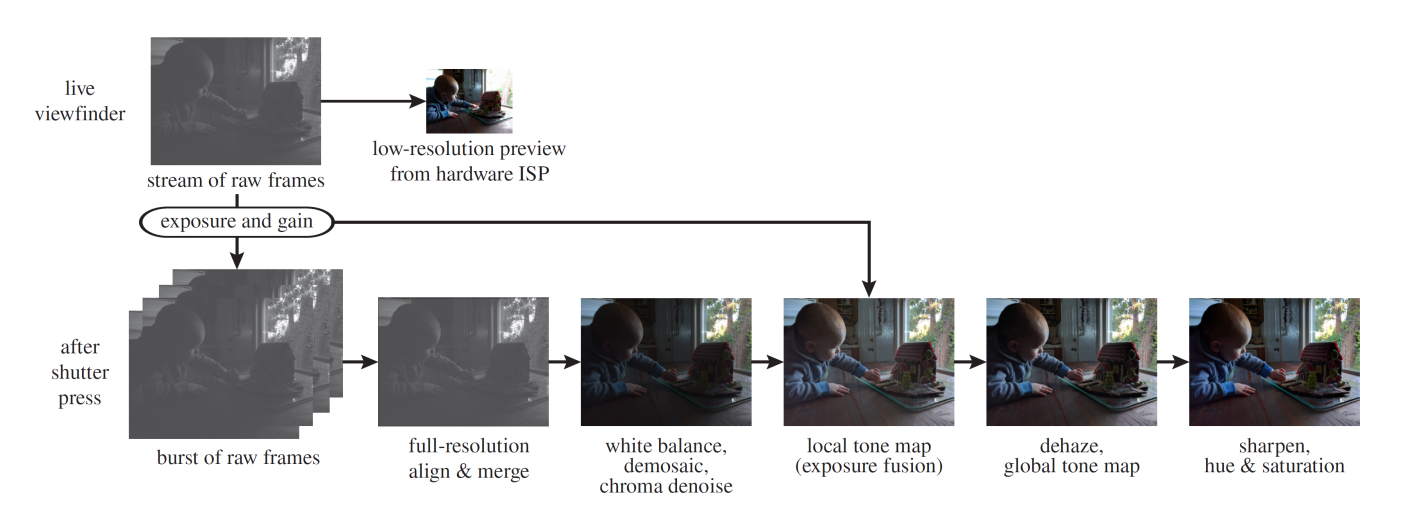

In order to widen the natural dynamic range of the hardware, modern photography relies on HDR (High Dynamic Range) technology. What this does is — the camera automatically takes multiple photos at different exposures, and then intelligently stitches them together. So, it takes a really dark photo and takes the non-burned highlights from that. Then it takes a really bright photo, where everything is burned, but the shadows are boosted and visible, so they can be cropped out and added to the final photo.

A modern HDR photo may consist of 5, 10, or even more frames captured at different exposures.

As you can probably guess, a lot can go wrong in that process. And typically, “bad” phone cameras won’t have the algorithms to properly stitch and recreate a good HDR photo. Here’s what common artifacts appear as:

- HDR halos – this is the most common, even on the most expensive of smartphones. However, they are definitely more prominent on cheaper or less effective phone cameras. Basically, this is the place where a dark object meets a highlight area. For example — the edges of buildings against a backdrop of the bright sky. The phone crops out the building from a frame it took at a really high exposure, and then attaches it to a skyline taken at a really low exposure, so the sky would be visible. That border between the building and the sky will show a soft white aura glow — this is the overlap between the two photos, the spot where you can see how much the exposure needed to be amped for the building to be captured.

- Flat objects – since HDR brings shadows up and tones highlights down, applying it aggressively can “flatten” objects. They no longer have a contrast between where the light hit them and where they have a natural shadow, so they look less pronounced, less realistic — a round cylinder may look very uncanny and almost as if it was drawn, instead of photographed.

- Unrealistic, amped colors – since HDR slaps together multiple captures of the same scene, a very common “HDR-ish” effect is that colors may get unnaturaly boosted or very skewed. Reds can become aggressive or needlessly vibrant. Alternatively, they may start looking more like orange. Grass can become a very bright shade of green that looks like it was filled in with crayons, instead of having a natural, earthy green to it. Skies can become a very saturated version of “baby blue”, invoking the feeling of a neon light instead of a natural sky.

Color science

While we are on the topic of color — color science is a very hotly discussed topic, even when it comes to big, pro-grade DSLR cameras. Imagine the discourse when we throw in a bunch of smartphones with AI doing the color science in the background!

Generally, here’s the thing we care about:

How realistic are the colors?

- Color accuracy — keeping the above in mind, most can agree that colors that are both unrealistic and saturated look unpleasant. In the smartphone world, reds and greens are often the worst offenders. Greens can overtake a photo and make it look like you’ve taken it in the Matrix. Reds can be unrealistically bright, so that they take attention away from the subject and ruin the realism of a photo. As bonus points, yellows and greens can be very skewed, and blues can appear deep and saturated.

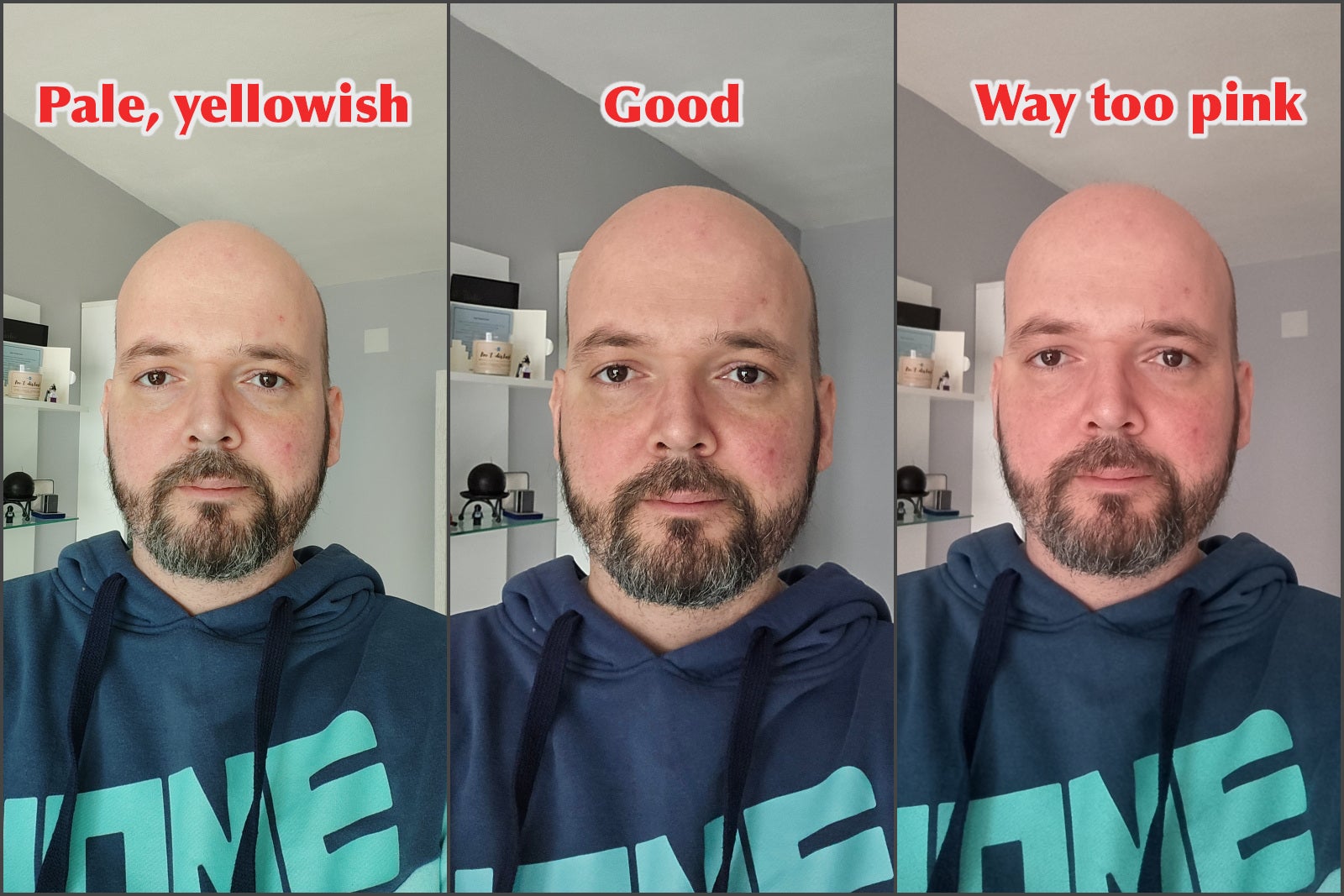

- Skin tone — a camera could have pretty realistic colors when shooting objects, nature, pets. But very often, human skin tone can look off. You can come out yellow-ish or desaturated, appearing pale and sickly. Or, you can come out looking pink, as if you were ashamed of the camera. Funnily enough, even top players like the iPhone can give you a pink face if the sunlight hits the right spots in a scene, tricking the algorithm to overtune the colors.

- White balance — without delving into things, white balance controls how warm (yellow-ish) or cold (blue-ish) an image can look. This setting is needed, because a scene can look very different depending on what type of light hits it. The way you perceive and remember a scene that is lit by a warm light will not be the same as the way a camera captures it, unless it has had its white balance set to compensate for the warmness.

Generally, “smart” and “good” algorithms are pretty good at automatically setting the white balance, so the photos end up closer to what you perceive. “Bad” cameras will go either too blue or too yellow on a scene. Which can ruin memorabilia — imagine taking a vacation photo at the sunny beach, but it ends up being inexplicably bluish, looking cold and un-fun. Objects that have warm colors — red, yellow, orange — can also appear unnatural too vibrant in a photo that otherwise has a cold white balance.

Lastly, some phones simply don’t capture colors that “pop” and the photos look desaturated, uninspiring, dull, and dreary.

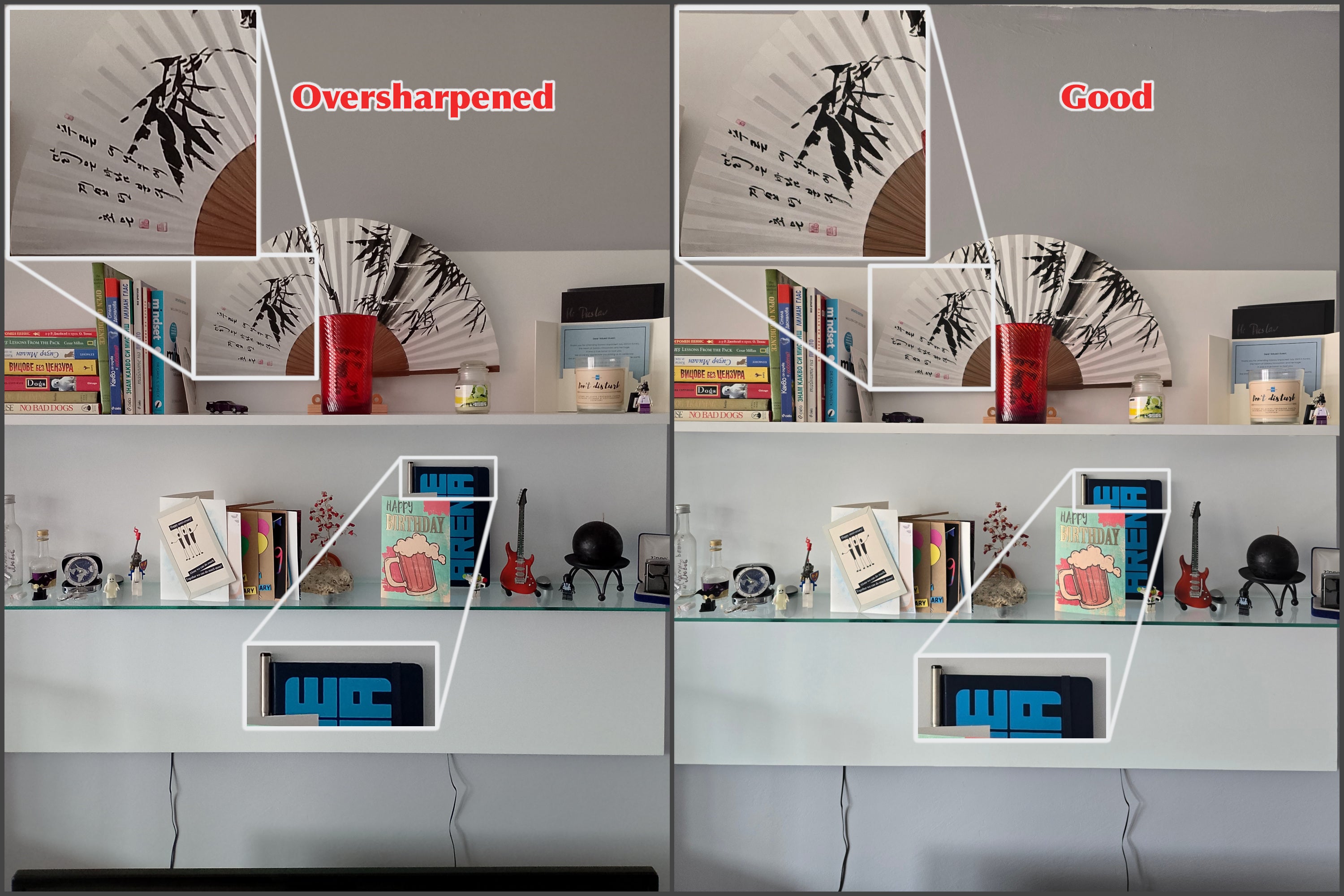

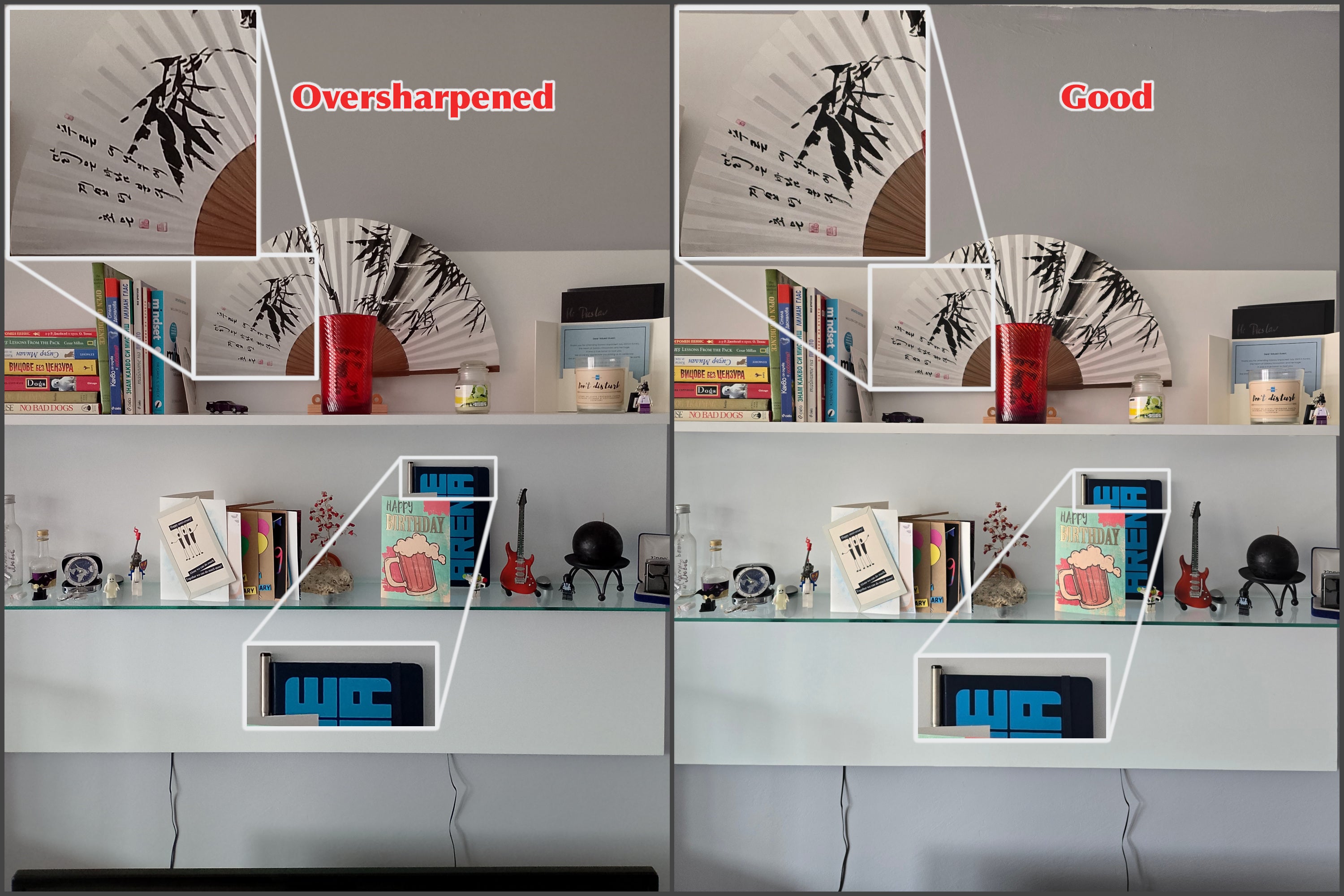

Let’s be honest — in 2024, sharpening — too much sharpening in photos — is the name of the game. Even big brands and leading phones do it. This is the process of increasing contrast along the edges of finer details, to give you the impression of a higher res capture, and greater detail in the photo. In the smartphone game, it’s somewhat needed, but it’s easy to go overboard with it, especially since you are letting an algorithm do it, and don’t have a human editor deciding how much sharpening is enough on a per-scene basis.

So, what does the so-called “oversharpening” look like? Edges, etchings, small dimples in rocks, wood grain, lines between bricks — they can start looking jagged, sharp (duh), and “fake”, as if they don’t belong in the scene. The latter effect is exacerbated by small white halos or outlines — kind of looking like a micro version the HDR halos discussed above — which underpin the spots where contrast was adjusted a bit too much.

Noise reduction

Noise is a permanent reality in camera sensors. There are two reasons you don’t see it most of the time. For one, most photos are taken in well-lit situations, so the “Signal to Noise” ratio is high, and the sensor doesn’t need a sensitivity boost to capture the photo. No sensitivity boost — less chance for noise to appear.

Grainy ISO noise, unprocessed

The second reason you don’t see it is because of noise reduction. Every smartphone camera needs and uses this. The small sensors behind small lenses simply can not collect enough light in short periods of time, which is why smartphone cameras are quick to boost their sensitivity as you go indoors, or the sun hides behind the horizon.

“Noise” in photos appears as grain, often around the darker areas of the photograph. Some artists like to leave it in for artistic expression, some people even re-add noise with digital editing. But smartphones, by default, will try to eradicate as much of that noise as possible.

So, a “good” phone camera will try to strike a balance between noise reduction and the complete eradication of details. I like the iPhone in this regard — it will often opt to leave in some graininess, but at least the photo looks more natural. Other phones may be so liberal with the noise reduction that the picture ends up looking like a cartoon.

Oversharpening vs overzealous noise reduction

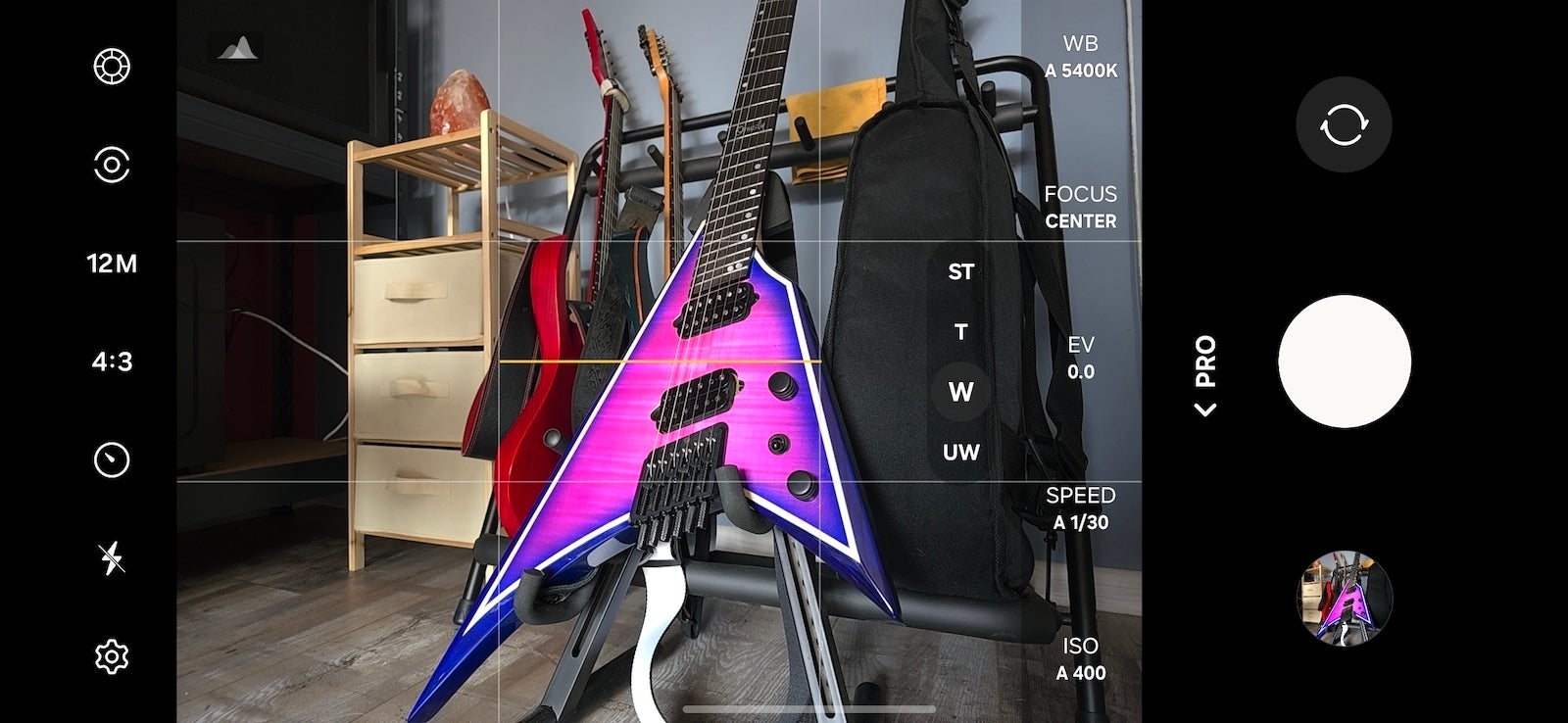

App experience

Last, but very definitely not least, it does matter what your experience with the app is. Do you have a virtual zoom wheel, so you can easily zoom in and out with a thumb swipe, instead of using “pinch to zoom” like a caveman? Can you easily turn vital things like the flash on and off, can you quickly toggle resolution and FPS for the video recording?

Focus speed, accuracy, stability

Obviously, focusing on the right thing is incredibly important if you want to capture a photo. Premium phone cameras will have laser autofocus, LiDAR, or some form of elaborate dual pixel focus to quickly snap on to the appropriate subject and keep attention on them unless you specifically tap on something else within the frame.

And low tier cameras — well, they are all over the place. They typically just choose a subject in the center of the viewfinder, or the one that appears to be closest. Then, you press that shutter button and just hope that the camera doesn’t change its mind in the last second. Oh, and it will have a second to think about it, because the last worst thing about bad phone cameras is:

Shutter speed

Typically, you don’t get pronounced shutter lag when shooting under bright sunlight, with a few exceptions. However, if it’s overcast, if you are indoors, or if it’s dark, a “bad” camera phone will take its sweet time taking that photo.

Why is that a problem?

Well, for one, the shutter lag may mean that the camera keeps the virtual shutter open for way too long, allowing for a lot of blur and shakiness while taking to snap a photo. In other scenarios, shutter lag is simply the phone “thinking” after you press that picture button. You wait and you wait, then you think the photo is snapped, you swing the phone around and it goes “click”. Great… your memorabilia is now a blurred picture of your shoes as you were shuffling the phone around.

Well, there you go, those are the main pillars of what would make a modern smartphone camera “good” or “bad”. Now, you can join the conversation at every party and not be confused by terms like “burned highlights”. Just kidding, we don’t go to parties. We would, we just don’t get invited to them.

#Galaxy #S24 #iPhone #bad #phone #cameras #wrong