The VotingWorks model won over some machine skeptics at the Concord event, like Tim Cahill, a Republican in the New Hampshire House of Representatives. Cahill said he’d prefer that all ballots in the state be hand counted but would choose VotingWorks over the other vendors. “Why would you trust something you can’t put your eyes on?” he told Undark. “We have a lot of smart people in this country and people want open source, they want transparency.”

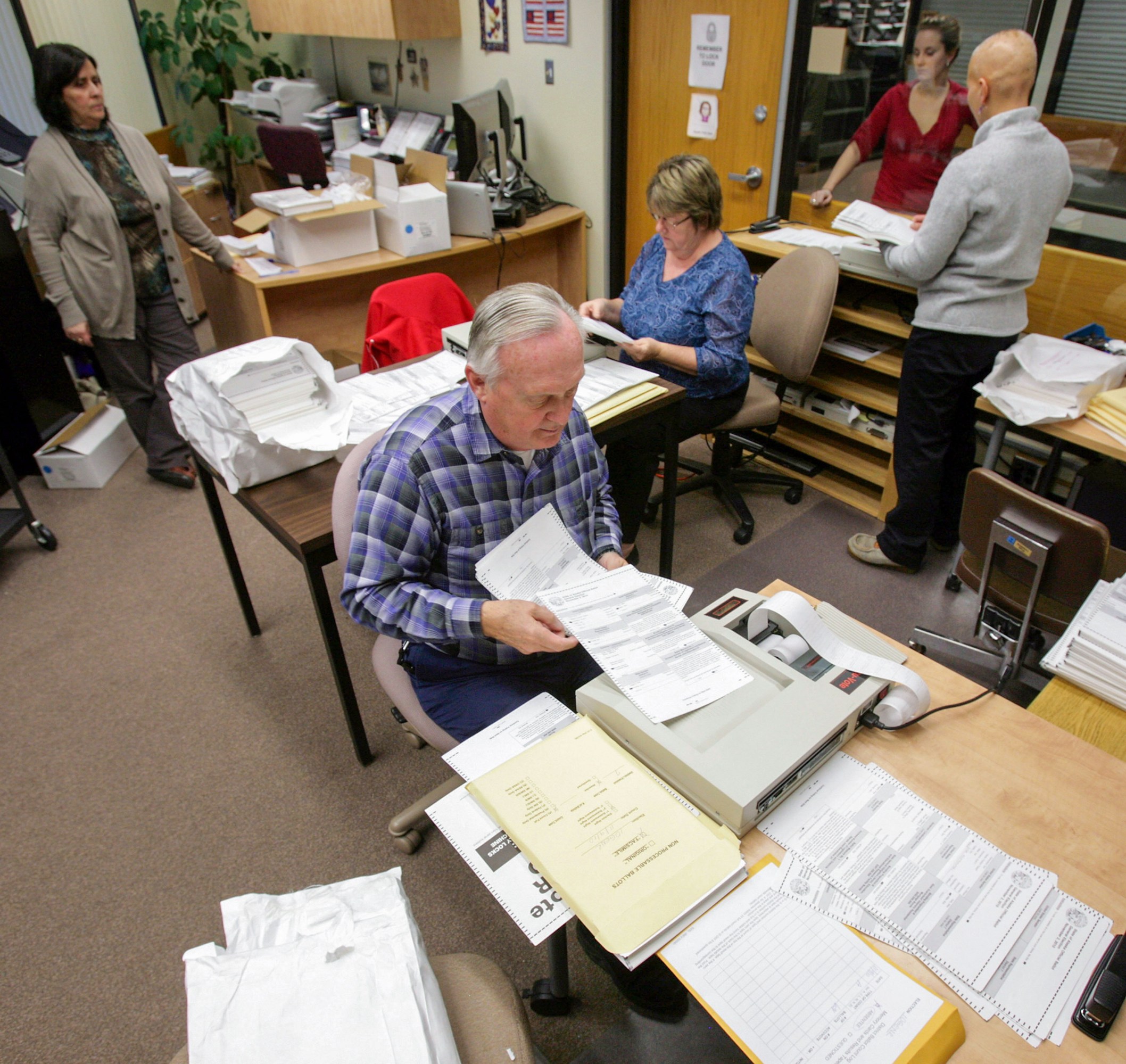

ERIC ENGMAN/GETTY IMAGES

Open source has found fans in other states, too. Kevin Cavanaugh is a county supervisor in Pinal, Arizona’s third most populous county. He says he started to doubt voting machines after watching a documentary, funded by the election denier Mike Lindell, claiming that the devices have unauthorized software that could change vote totals without detection. In November 2022, Cavanaugh introduced a motion to increase the number of ballots counted by hand in the county, and he told Undark he’d like a full hand count. “But, if we’re using machines,” he added, “then I think it’s important that the source code is available for inspection to experts.”

Back in Concord, Adida appeared to be persuasive to the public at large — or at least those invested enough to attend the event. Of the 201 attendees who filled out a scorecard, VotingWorks was the most popular first choice. But among election officials, the clear preference was Dominion. Some officials were skeptical that open-source technology would mean much to people in their towns. “Your average voter doesn’t care about open source,” said one town clerk.

Still, five towns in New Hampshire have already purchased VotingWorks machines, some of which will be used in upcoming March local elections.

Two main factors determine whether someone has faith in an election, said Charles Stewart III, a political scientist at MIT who has written extensively about trust in elections. The first, which affects roughly 5 to 10 percent of voters, is a negative personal experience at the polls, like long lines, rude poll workers, and problems with machines, which can make the public less willing to trust an election’s outcome.

The second, more influential factor affecting trust is if a voter’s candidate won. That makes it supremely difficult to restore confidence, said Tammy Patrick, a former election official in Maricopa County and the current CEO for programs at the National Association of Election Officials. “The answer on election administration — it’s complex, it’s wonky, it’s not pithy,” she said in a recent press conference. “It’s hard to come back to those emotional pleas with what the reality is.”

Adida agrees with Stewart that VotingWorks alone isn’t going to eliminate election denialism — nor, he said, is that his goal. Instead, he hopes to reach the people who are susceptible to misinformation but haven’t necessarily made up their minds yet, a group he describes as the “middle 80 percent.” Even if they never visit the company’s GitHub, he says, “the fact that we’re putting it all out in the open builds trust.” And when someone says something patently false about the company, Adida can at least ask them to identify the incriminating lines of source code.

Are those two things — rhetorical power and a commitment to transparency — really a match for the disinformation machinery pushing lies across the country? Adida mentioned the myths about legacy vendors’ machines being mis-programmed or incorrectly counting ballots during the 2020 election. “What was the counterpoint to that?” he asked. “It was, ‘Trust us. These machines have been tested.’ I want the counterpoint to be, ‘Hey folks, all the source code is open.’”

Spenser Mestel is a poll worker and independent journalist. His bylines include The New York Times, The Atlantic, The Guardian, and The Intercept.

This article was originally published on Undark. Read the original article.

#open #source #voting #machines #boost #trust #elections